Explaining Brain Death and Organ Donation to Children

Guest post by: Kristen Lawrence, Certified Child Life Specialist, Emergency Department

This post includes affiliate links. At no extra cost to you, I earn a small commission when you purchase items I use and recommend by clicking the links below. Thank you for your support!

As a child life specialist, I am always learning new things and developing creative and appropriate ways to educate about procedures, diagnoses, medical equipment, medical terminology- the list goes on and on. I know what it means to jump from patient to patient and to learn as I teach, and I’ve developed an ability to appropriately adapt my intervention to best meet the needs at hand. That being said, I will never forget the day I was first asked to explain brain death and organ donation to school-aged children.

Having had supported multiple families through end of life situations throughout my career, I was familiar with explaining death to children; however, brain death and organ donation added another layer to this already difficult topic. Knowing how difficult this topic is to address, I have outlined my top pieces of advice that parents, caregivers, and professionals can use to empower children in understanding brain death and organ donation.

Brain death is a very abstract concept, especially if the patient was not previously sick, appears to be breathing due to a ventilator, and does not look hurt. Assess what the child understands about the role of the brain, the patient’s hospitalization, and need for medical equipment. Provide very concrete and honest information.

Start by helping the child understand the role of the brain. Assess what the child knows about what his/her brain does, and provide information that addresses the obvious role of the brain to a child, such as helping the child to think in order to do their homework, read, etc. Then address the brain’s other roles, such as “being the boss of the body” and “telling the body what to do and how to work,” including "telling the heart to beat, the nose to breath, and the legs to walk, etc."

Next, explain that the brain has to be healthy in order to tell the body what to do. Talk to the child about their understanding of the patient’s injury/illness and explain that the patient’s brain was “very hurt” due to the accident/illness/injury. Emphasize that the doctors did everything they could to help the patient’s brain, but that the patient’s brain was “so hurt,” that it could not get better, and that the patient’s brain had died/is dead. “Dead” is often seen as a harsh word, but it is the most accurate and concrete language to use with children.

As death is a difficult concept for children to understand, brain death can often be confusing for children, especially since patients who are organ donors are connected to mechanical support until their organs are able to be surgically removed. It is not uncommon for children to question why the patient is “breathing.”

Reiterate that the patient’s brain is dead, meaning the patient’s brain will never again be able to tell the patient’s body how to work, so the patient will never wake up. Because the brain was so hurt and is not able to tell the body how to work, the patient’s body is receiving medicines and is connected to machines to tell the patient’s heart to beat and lungs to breath. It is VERY important to emphasize that the machines are telling the other parts of the patient’s body to work, but the patient’s brain is still dead. This means the patient will never be able to wake up, talk, laugh, think, or live again. This is often difficult to say, but it is important because many children will think that the patient can still be alive as long as they are connected to machines at the hospital.

Tell the child that the patient will not be able to come home from the hospital, and that even though the patient’s brain died, other important parts of the patient’s body still work. Explain that the patient’s heart and other organs are still healthy, but they will never work in the patient’s body again. I often find it helpful to specifically name only one familiar organ, such as the heart, in order to minimize information overload and keep it as concrete as possible.

When introducing organ donation, share that sometimes other kids or adults have hearts or other organs that are not healthy and do not work how they are supposed, but that these kids and adults can “get new hearts" from other people whose hearts are still healthy, but whose brains are dead and "don't work" anymore, such as the patient. Reiterate that, because the patient’s brain is dead, the heart and other organs will never work in the patient’s body again, but they can work in the body of someone whose brain is alive, healthy, and working.

Children will often question how the organs are removed, so a brief introduction of surgery is typically needed. Share that the patient will go to a part of the hospital to have surgery which means doctors will make a “small cut” in the patient’s body to take out the patient’s heart and other organs. Explain that a “small cut” will also be made in another child’s or adult’s body, so the organ can be put in their body to replace the heart or other organ that does not work. Further educate that once the heart is in someone else’s body, that "person’s brain will be able to tell the heart how to work, because their brain is healthy."

It is important to also ensure that the child knows that the patient will not return to the hospital room. Before the patient is taken to surgery, offer the child opportunities to say goodbye to the patient. The child may just want time alone with the patient, or they may want to write a letter or draw a picture that can stay with the patient. Allow the child a sense of control by ensuring that the options for saying goodbye are feasible and comfortable for the child.

This conversation is a very difficult one and it is likely that the child will have many questions. It is okay to admit you do not know the answer to something if the child has a difficult question. Seek out appropriate support, such as a child life specialist if available, to provide guidance through this conversation. Be as open and honest as possible throughout the conversation. It is likely that the child will continue to ask questions long past the conversation, so ensure that answers to these questions remain consistent and honest.

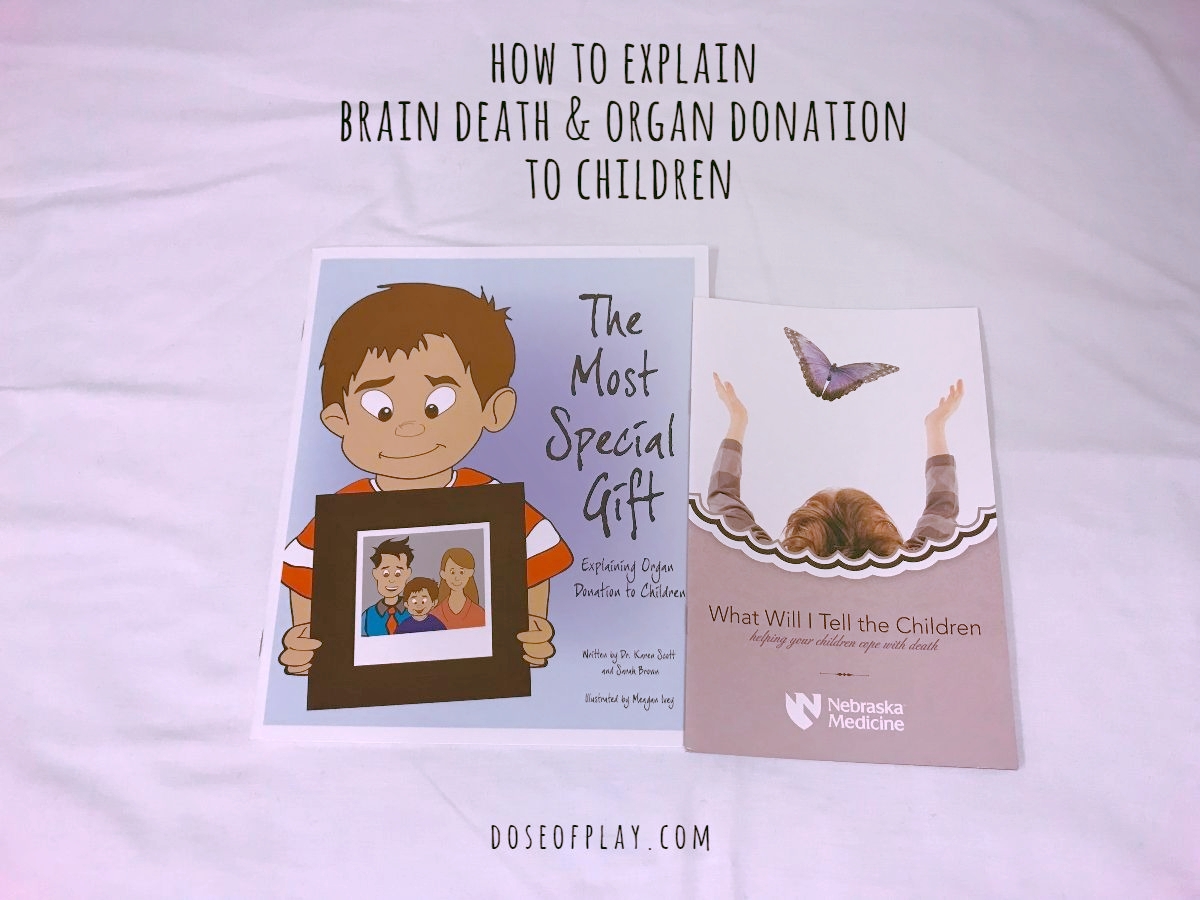

For additional support in helping to answer children’s questions regarding brain death, death, and organ donation, I recommend the following resources:

The Most Special Gift: Explaining Organ Donation to Children. Written by Dr. Karen Scott and Sarah Brown, and illustrated by Meagan Ivey.

What Will I Tell the Children: Helping Your Children Cope with Death. Published by Nebraska Medicine. Free Download.

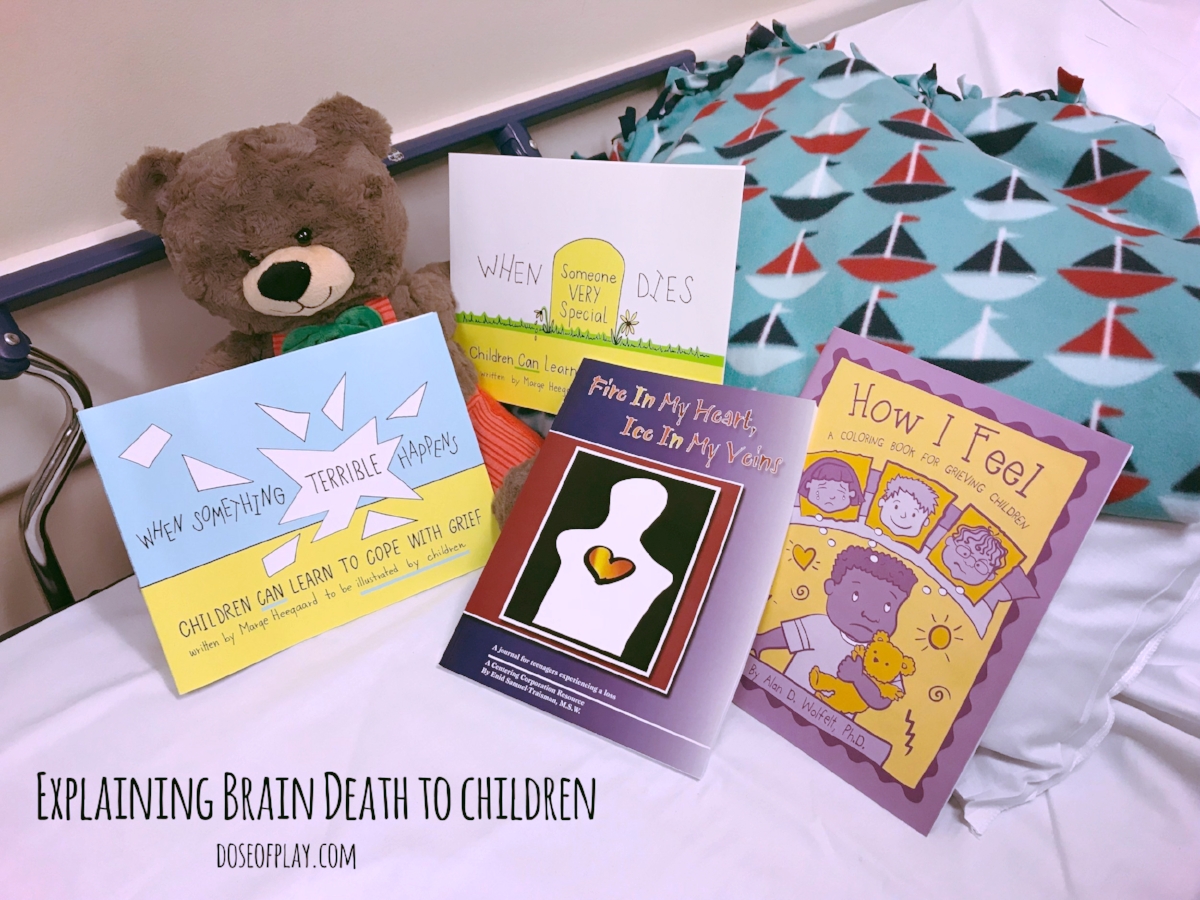

In addition, the following grief journals are helpful in allowing children to process their grief and their understanding of the patient’s death.

Preschoolers

How I Feel: A Coloring Book for Grieving Children. Written by Alan D. Wolfelt, Ph.D. You can find a care package here.

School-aged

When Someone Very Special Dies: Children Can Learn to Cope with Grief. Written by Marge Heegaard

When Something Terrible Happens: Children Can Learn to Cope with Grief. Written by Marge Heegard

Teenagers